-

Beyond China's Biggest Cities, A Complex Boom for Brands Is Seen to Roll On

外國品牌在中國競爭的新戰場Posted by Abe Sauer on January 15, 2013 11:55 AM指導者 / 總編輯 張蕙娟摘譯者 / 賴俞臻中國城市因行政及政治因素分為五線:第一線為大都市,包含上海、北京、廣州、深圳等,為外國品牌設點之大宗;第二線約有25個城市,為各省的首都及富有的城市,例如天津、青島及大連;第三線屬較西方內陸的城市如蘭州等;第四線屬自治區。

第三線城市目前已成為外國品牌在實品體驗區以及網路購物競爭的主要戰場,然而根據奧美集團的研究指出,後段城市和第一線的消費力仍有差距,但往第一線城市流動的勞工也間接促進了第三、四級城市的消費能力。而第一線城市也成為後線城市的時尚指標及效法對象。目前各品牌在中國的行銷策略都以品牌價值的強調及確立作為和山寨品的對抗模式。

An expansive new book calls China's lower-tier cities "arguably the most important consumer segment in the world," joining a growing chorus that points to opportunity for growth there in 2013.

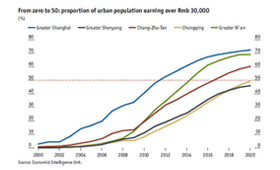

Last year, China's population flipped from majority rural to majority urban, with most of the newly urban living in cities classified as Tier Two — smaller cities and provincial capitals that nonetheless have hundreds of thousands of residents. Such cities, along with their lower-tier counterparts, are projected to be the source of much of the predicted 11 percent growth in China's retail sales sector over the next eight years. These cities that will out-boom a booming nation, and feature growth in youth consumption as the populations of Shanghai and Beijing age.

And the consensus is that brand latecomers will be punished severely.For administrative and economic reasons, China's cities are ranked in five "tiers" of government. Lists may differ because tiers can be defined by GDP or population.

Tier One always includes Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou — cities through which foreign brands almost always enter China. Shenzhen is often placed in Tier One as well.

Tier Twos (totaling about 25) are provincial capitals and well-heeled cities like Dalian, Qingdao, Chongqing and Tianjin. Tier Three (totaling over 220) are usually more western, landlocked prefecture cities like Zhengzhou and Lanzhou. Tier Four (totaling over 300) are county municipalities.

Two years ago, the China Normal project specifically targeted the market landscape in lower tier cities — which lack a Starbucks, for instance. The study reasoned correctly that "in the minds of most young Chinese, big cities have Starbucks." (It's no surprise that Starbucks is rushing to reach into these tiers. Meanwhile, Apple recently opened its first store in the west and, while woefully behind its 2010 schedule, is planning more.)

The property market in Tier 3 cities is the coming "major battlefield" in China's real estate. As saturated First Tier luxury consumers quickly become more discerning, the lower-tier luxury markets are exploding. But, as Ogilvy ↦ Mather China's new book, "China Beyond - Change & Continuity," reports, these lower tiers are distinct from Tier One cities. These consumers, for example, are far more "tight-fisted," according to Ogilvy & Mather.

However, they are just now waking to the joy of buying. In a recent presentation to the China business intelligence agency Z.H. Tank, Tan ("Andrew") Yi, marketing director for Reckitt Benckiser, said the $45 billion that migrant workers in Tier One cities send home to rural areas annually is giving many rural residents the ability to "shop as a leisure activity" for the first time. This early impact on Tier Three and Tier Four economies will be followed by an income boom as more economic activity moves inland and west. Thanks to huge spending on infrastructure modernization in lower tiers, this boom will soon be fueled by a growing middle class. Companies looking to escape increasingly expensive coastal locations have been enticed by new infrastructure that did not exist five years ago — and the same infrastructure is enticing workers.

But this new lower-tier middle-class presents a challenge for brands looking to ride the boom in China. These consumers have not been in complete consumption darkness. For example, China's boom in online shopping means many brands have already made it to third- and fourth-tier cities despite lacking an active presence there.

"Already, consumers in these smaller cities are ordering brands that are not available in physical stores: fashion, cosmetics, consumer electronics, baby products," Kunal Sinha, chief knowledge officer of Ogilvy & Mather China, told Brandchannel. And that means a variety of strategic changes for brands, he said.

"Marketers will realize that they may not need as many physical stores as they had previously thought would be necessary," Sinha said. "Instead, they may need to provide only a few 'experience zones' where lower tier consumers congregate."

Efforts to crack China's lower tiers are leading to unique strategies. When the pharmaceutical maker Roche saw that few in these areas could pay for its drugs, it partnered with insurer Swiss Re to sell private insurance to Chinese consumers, which would then cover the costs of Roche's drugs.

One of the book's more unique findings is how counterfeit brands have gone upmarket in lower tiers. Instead of faking durable goods, opportunists are building luxury hotel knock-offs including "Hiyatt" and "Marvelot" hotels. Designer Dsquared2 now faces competition from Ssquared. Legally — as we've noted about Jordan knock-off "Qiaodan" — brands often have little recourse.

Sinha calls these fakes "part of the learning experience" for lower-tier consumers. Yet, he said, a new development is that many of these consumers are knowingly choosing to buy a fake "because they are questioning the premium that a 'real' brand might command." One of the study's informants "saw no reason to pay five times more for a real Puma t-shirt, when a fake one would do just the job," he said.

To combat this tricky sentiment, Sinha suggested that brands "find a way of justifying the premium." For example, a brand might imply through messaging that "the user of a fake brand is somehow a 'fake person,' " he said. However, Sinha advised using humor and warned against antagonizing consumers. Indeed, a brand should hope that a guest at "Marvelot" is just a future guest at Marriott who doesn''t yet know better.

Tier One shoppers still spend significantly more per capita than lower-tier counterparts. A recent Bain study found that in 2011, "Tier 1 shoppers spent an average RMB 10,700 per household compared with RMB 5,600 for Tier 5 city shoppers."

But it's the sheer numbers of consumers in the lower tiers that will overwhelm. And Tier One has a important role to play here as well.

"Most lower tier shoppers look at key opinion leaders, bloggers and reviewers — most of whom live in the bigger cities — for advice, and their opinion is trusted," said Sinha. "Returnees from the first-tier cities are also looked upon as advisors."

So money being sent home has been replaced by the opinions of returning consumers as a key driver of economic growth. Making the challenge all the harder, it seems that brands looking to develop the lower tiers should be wary of doing so at the expense of those at the top.

摘譯自BrandChannel:

http://www.brandchannel.com/home/post/2013/01/15/CHINA-TIERS-011513.aspx